Data Rounding and Why You Should Care

Many people believe that it makes no sense to store data at a resolution that is more precise than the resolution that it can be observed.

For example, it is believed that if you round water level to the nearest millimeter then the value will never be more than half a millimeter from the original.

This idea was accepted as a reasonable compromise in the 20th century, and data management systems from that era were designed around it as a core concept.

Modern data processing requirements, however, demand a different approach.

In order to understand why modern data management systems all store data to double precision we must consider the distinction between storing and reporting of data

Data storage is considered to be lossy if inexact approximations and partial discarding of data result in a loss of information.

Data reporting is the presentation of final results. Rounding the final result to a sensible resolution can be very useful.

Rounding to a given level of numerical precision communicates the limit of useful resolution to the end-user.

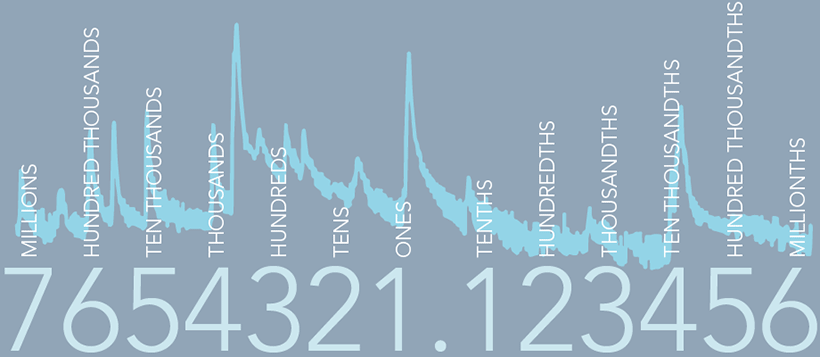

A value expressed as 10 infers that the ‘truth’ is somewhere between 9.5 and 10.5, whereas a value expressed as 10.0 infers that the truth is somewhere between 9.95 and 10.05, and this is a very important and useful distinction. Rounding data to a meaningful resolution facilitates meaningful analysis and data interpretation. For example, given a column of data at very high resolution, the position of the decimal place in each number can be lost in the visual noise, whereas if data are presented at a resolution of just a few digits then order of magnitude errors are readily identifiable. Finally, rounding of final data makes any final reports formatted for printing look tidy and professional.

Whereas rounding is merely useful for reporting the final data product, rounding is an inevitable consequence of digital data acquisition.

If we assume that the observed phenomena is a continuous process, then the analog signal must be discretized to create a digital signal. There is irreversible loss of information when we digitize that signal to store it on a datalogger and communicate those data to a data management system.

As a general rule, data are acquired and communicated at a similar resolution to that by which independent observations can be used to validate the result. For a continuous water level signal it is convenient to record values to the nearest millimeter. Acknowledging that this discretization of the underlying signal is only an approximation, this is a pragmatic limit because we have no empirical way of verifying that any more precise increment of water level is actually true.

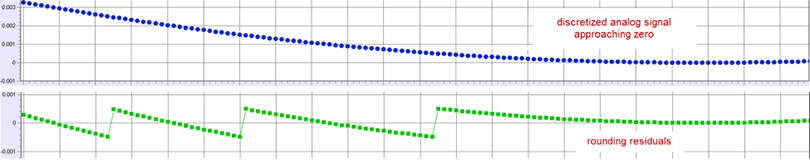

Figure 1. The effect of approximating an analog signal to a 3 decimal place digital representation as the signal approaches zero, illustrating that the residuals are scale-dependent and serially auto-correlated.

We can accept that these errors are not normally distributed (i.e. all errors over the full range from -0.5 to +0.5 millimeters are equally probable) and that the error is scale independent (i.e. the error magnitude becomes disproportionately large for very small numbers) and that the error is highly structured (i.e. the error for any point is strongly correlated with the errors of the preceding and succeeding points) if, and only if, we do no further rounding of intermediate values in the processing chain.

Clearly, data rounding is a necessary condition for getting analog data into a data processing chain and data rounding is a desirable condition for data leaving a data processing chain. Less clear is the harm that can be done by rounding of intermediate values within a data processing chain.

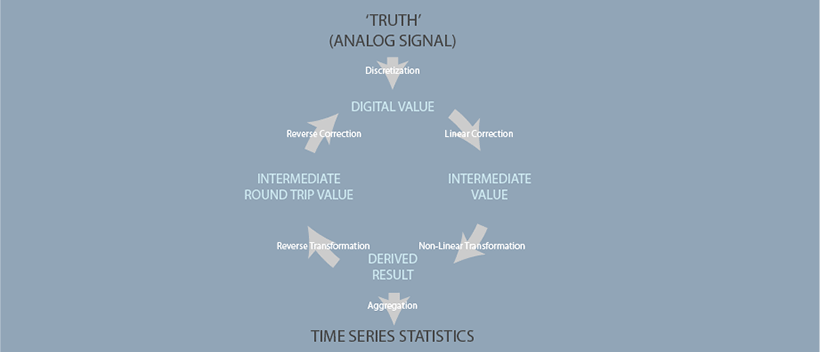

One way of evaluating this harm is submitting the data to a round trip to see if information surviving the data processing system is identical to the information at source, which can be evaluated by reversing all events in the data processing chain (Figure2).

Figure 2. A schematic for estimating the ‘lossiness’ resulting from intermediate rounding of values to some specified numerical precision.

If the errors that are inherently introduced by digitizing the analog signal were independent (in both time and proportionality) and normally distributed then it might be expected that it would be possible to apply linear corrections and non-linear transformations to the data without fundamentally altering the error structure and hence, conservation of information.

However, this is not the case. In a round-trip analysis comparing the effect of rounding all intermediate values to double precision vs. storing linearly corrected values to 3 decimals and non-linearly transformed values to 3 significant figures it can be shown that the error structure is irreversibly transformed by data processing.

One might hope that the errors from intermediate rounding would all magically average out when time-series statistics such as for daily and monthly averages and extremes are calculated. Unfortunately, this is also not the case.

The error structure evident at the unit value level will be amplified and magnified by data processing and can be highly impactful on the statistics that people in water scarce regions care the most about – low extremes.

Even when data are stored at double precision, there can be a very small bias introduced at every step in the data processing chain from tie-breaking. For this reason modern data management systems (at least AQUARIUS) use unbiased tie-breaking rules.

However, if the common round half up tie-breaking rule is used for intermediate rounding to the desired end-result resolution then one will find that one value in ten will be biased slightly high. The more steps there are in the processing chain the greater the net positive bias will grow. This systematic, and hence entirely unnecessary, bias can be identified in low flow statistics where the data processing system does not preserve double precision data integrity.

In summary, we can accept that data rounding is necessary for digitization of an analog signal.

We can demonstrate that rounding of intermediate values in a data processing chain creates disinformation. We can explain why rounding for reporting of final results is desirable. But this begs the question: what are final results and for whom?

This last question is becoming increasingly germane as we shift the paradigm from data reporting to data sharing.

In the 20th century, it was pretty clear that data publication (most often formatted for hard-copy printing) was the final result of the data processing chain. However, in the modern era the unit value discharge may be an intermediate value for computing another variable (e.g. suspended sediment), which may be an intermediate value for some other variable (e.g. contaminant loading).

Perhaps it is time to distinguish between ‘publishing’ rounded values versus ‘sharing’ double precision versions of our data.

In the data sharing paradigm it is certainly possible to include the metadata needed to correctly interpret meaning explicitly rather than continue to provide that information implicitly by the use of rounding rules. The choice should be yours.