Extreme Gauging – How to Extend Rating Curves With Confidence

Extreme flows are extremely hard to gauge, hence we get very few gaugings to accurately define the top-end of stage-discharge rating curves. This is a problem. Whereas empirically calibrated functional relationships can be trustworthy for the purpose of interpolation, they can be notoriously unreliable for extrapolation. One needs to be very careful about extrapolating any rating curve to an ungauged extreme.

Extreme flows can be characterized as infrequent, short duration, high magnitude events.

- Rapid response is required to be at the right location, at the right time.

- Risk factors, both for site access and with respect to proximity to the water, are highly consequential and have increased likelihood due to environmental factors.

- The factors that contribute to extreme events (intense storms) and hydraulic factors (turbulent flow, heavy debris) are distinctly unfavorable both for humans and measurement equipment.

- Equipment that may be perfectly adequate for measurement of ‘normal’ flow may be completely or partially inadequate for extreme flow.

Altogether, there are a lot of perfectly good excuses to run a gauge for years, even decades, without ever gauging an extreme event. In the absence of gaugings any extrapolation has to be guided by human judgement.

But how good is your judgement if you have never gauged the extreme?

It is often the case that a hydrographer will err on the side of ‘caution’, pulling the curve a bit to the left to provide a ‘conservative’ estimate of the extreme flow. However, if as a data consumer your job is flood risk management a ‘conservative’ estimate is one that over-estimates peak discharge.

In the absence of consensus on what ‘conservative’ means, it would clearly be better to pin the top-end of the rating to gaugings to provide an accurate estimate of peak flow. Jerome Le Coz from IRSTEA is working to systematically take away all of your excuses for not doing exactly that.

I, for one, don’t need any more convincing that the time has come for hydrometric monitoring authorities to start large-scale investigations of these techniques to develop standard operating procedures and best practices in order to train stream hydrographers everywhere on how to obtain consistently reliable results with safe procedures and protocols.

It is important to note that these techniques don’t replace conventional measurement techniques.

They have their strengths and weaknesses. PSVR is not reliable below 0.7 m/s. LSPIV does not work in the dark. They both require surveyed cross-sections and an estimate of a surface velocity coefficient. Non-intrusive gaugings come with larger uncertainties than conventional gaugings. However, they come with far less uncertainty than no gauging.

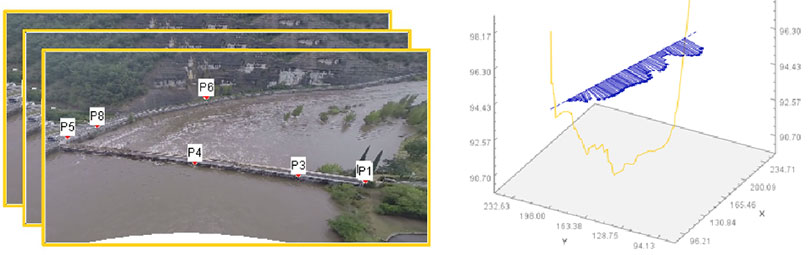

LSPIV gaugings can even be done with home videos found on YouTube for post-event analysis. Camera angle and positioning can be optimized by deployment from a drone, which creates opportunity to the operator to be far away from moving water while doing the gauging. Similarly, it is often the case that helicopters are used for site access during extreme events. With this technique the operator does not even need to land to obtain a gauging.

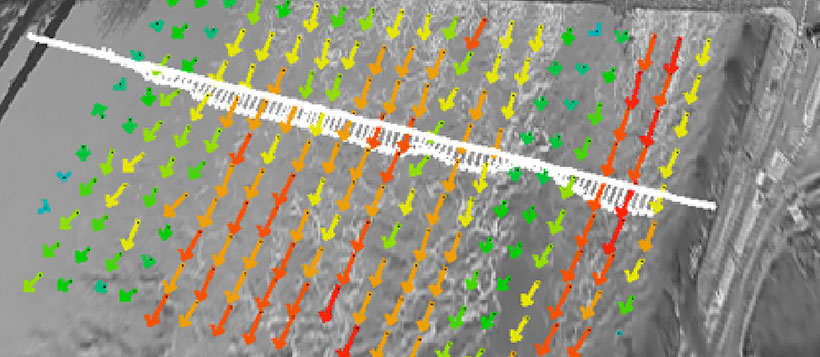

Image processing for LSPIV can be done with software jointly developed by EDF and IRSTEA that can be downloaded for free. The ‘father’ of the LSPIV technique is Prf. Ichiro Fujita, Kobe University, Japan (Fujita et al. 1998) but enabling technology has come a long way since then. Further information about the technique can be found in this presentation to the Riverflow 2014 conference and in this article in the Journal of Hydrology.

If you do adopt non-contact gauging techniques for the measurement of extreme flows, don’t be surprised if you find that your existing curve extrapolations need to be re-analyzed. It is a GCOS principle that a suitable period of overlap for new and old observing systems is required but this is a bit different because adoption of this technology will add new information about the entire history of peak flow events.

The Rating Workshop in Christchurch New Zealand had a breakout session on re-analysis of past ratings confirming that while all participants have protocols for retrospective change of ratings there is diversity on how much ‘discovered’ error is enough to trigger a change.

It is widely agreed that in order to be defensible, especially in court, there must be a system in place to eliminate any known errors in the data.

It is rare that a technology comes along that can not only improve the quality of data post-implementation but also pre-implementation. These technologies that enable extreme gauging, I predict, will be a disruptive change.